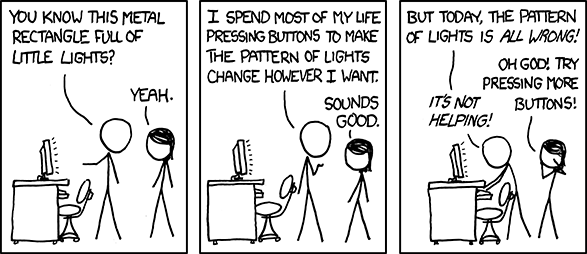

Here is a scenario that you have probably already experienced: you intervene on a new project and your first reflex is to read the README file to understand what is going on, then starting your development. You begin to realize that this README is no longer very up-to-date and that some versions have changed. You advance by trial and error then give up by asking for help from another developer to finish your installation.

With a bit of luck, we can find the correct commands after few tries to install the project.

It is safe to say that a bad introduction on a project has never increased a developer’s motivation. And yet, we let these things linger in the hope that a developer will write a README up-to-date until the next major change on the project.

Make is a program that you have probably manipulated since it has existed since 1976 and its use is almost mandatory with C. Its main use case is the automation of the compilation phase of a project. It has become a standard in the world of the computer development with its simplicity and the enthusiasm it has received.

In fact, to launch the compilation of most C projects (the Linux kernel for example), we just need to run the make command in a shell.

Most of these projects are equipped with a Makefile at the root.

Make can organize the compilation phase with a recursive manner giving a fancy description of it in the

Makefile.

If I mention this tool to you today, it is because it is usable on all moderns operating systems.

It can automate the installation of a project regardless of the technologies used on it.

In fact, make will use the default interpretor of the system to execute the commands described in the Makefile.

Let’s take a real-world example, a Java Spring MVC project with a Tomcat instance as a Docker container.

We start by creating a Makefile file at the root of the project to write several rules.

They are made up as follows:

<name of the rule>: <lists of prerequisites to execute before this rule>

<command_1>

<command_2>

...

# We can also put conditions:

ifneq (...)

...

endif

NB: Complete documentation on syntax

We create a first rule which will allow you to check if you have all necessary tools to build/start the project.

JAVA_VERSION = 13

check:

ifneq ($(shell java -version 2>&1 | grep $JAVA_VERSION > /dev/null; printf $$?), 0)

@echo -e "\e[0;31mIncorrect Java version, please use JDK$JAVA_VERSION }.\e[0m"

@exit 1

endif

ifneq ($(shell command -v mvn 2>&1 | grep mvn > /dev/null; printf $$?), 0)

@echo -e "\e[0;31mPlease install Maven.\e[0m"

@exit 1

endif

ifneq ($(shell command -v docker 2>&1 | grep docker > /dev/null; printf $$?), 0)

@echo -e "\e[0;31mPlease install Docker.\e[0m"

@exit 1

endif

The @ character allows to make invisible the launched commands in the standard output.

Without Java 13, the

make checkcommand tells me that I don’t own the correct Java version for this project.

Once the tools verification done, we define the automatisation of the install phase:

# An installation example with a Java project with a static dependency.

install: check

docker-compose up -d

mvn install:install-file -DgroupId=com.proxiad -DartifactId=utils -Dversion=1.0.0 -Dpackaging=jar -DgeneratePom=true -Dfile=jars/proxiad-utils.jar

mvn clean package -DskipTests

build: check

docker stop tomcat

mvn clean package

docker start tomcat

docker logs -f --tail 100 tomcat

The build rule will:

- Run the

checkrule as prerequisite. - Stop the Tomcat container.

- Compile a new

.warfile. - Restart the Tomcat container by following the last 100 lines of the container’s logs.

With this prerequisite definition, we know that the build rule cannot be executed until our envrionment is set to the correct versions.

We add the following two rules:

cleanwhich deletes the build files and the container.formatlaunching the project formatting with spotless :

clean:

docker stop tomcat > /dev/null

docker rm tomcat > /dev/null

git reset --hard && git clean -dffx

format:

@mvn spotless:apply

We therefore get the following Makefile file:

JAVA_VERSION=13

all: build

install: check

docker-compose up -d

mvn install:install-file -DgroupId=com.proxiad -DartifactId=utils -Dversion=1.0.0 -Dpackaging=jar -DgeneratePom=true -Dfile=jars/proxiad-utils.jar

mvn clean package -DskipTests

build: check format

docker stop tomcat

mvn clean package

docker start tomcat

docker logs -f --tail 100 tomcat

clean:

docker stop tomcat > /dev/null

docker rm tomcat > /dev/null

git reset --hard && git clean -dffx

format:

@mvn spotless:apply

check:

ifneq ($(shell java -version 2>&1 | grep $JAVA_VERSION > /dev/null; printf $$?), 0)

@echo -e "\e[0;31mIncorrect Java version, please use JDK$JAVA_VERSION }.\e[0m"

@exit 1

endif

ifneq ($(shell command -v mvn 2>&1 | grep mvn > /dev/null; printf $$?), 0)

@echo -e "\e[0;31mPlease install Maven.\e[0m"

@exit 1

endif

ifneq ($(shell command -v docker 2>&1 | grep docker > /dev/null; printf $$?), 0)

@echo -e "\e[0;31mPlease install Docker.\e[0m"

@exit 1

endif

The

allrule is associated with execution of themakecommand without arguments.

With some imagination, we could integrate a install-front rule and a run-front rule handling the installation and the build of a front-end in a subfolder ui.

install-front:

cd ui && npm install

run-front:

cd ui && npm run start

Make is a standard. This is what makes it powerful. If someone looks at a new project and sees that a Makefile has been made, they will determine that it will be up-to-date and functioal since previous developers have used it. However, take precautions during your first uses, this is very capricious about syntax.